The Wolverine Size of a Baby Wolverine Actually a Baby Wolverine Signs

Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2014

Wolverines: Behind the Myth

By Riley Woodford

Wolverine release: This wolverine was collared and had just recovered from the immobilizing drug.

The wolverine'southward reputation precedes information technology.

In Marker Trail's Book of Animals, Ed Dodd writes: "Savage ferocity combined with mischievous cunning has fabricated the wolverine an object of hate and dread amidst trappers."

In Mammals of Northward America, Vic Cahalane recounts the legendary prowess of the wolverine equally fact: immensely strong and known to bulldoze bears and mountain lions off their kills (two or three at a time, fifty-fifty); capable of taking downwards a bear in a fight; and bad-tempered loners that will destroy a cabin out of sheer deviltry.

Fact and Fiction

Fish and Game researchers Howard Gilded and Mike Harrington are studying wolverines in Due south-cardinal Alaska. In recent years they've captured 18 wolverines and equipped them with GPS tracking collars to better understand their movements and numbers. Wolverines are impressive, but much of the reputation is exaggerated.

"They've got such a bad rap," Harrington said. "I've had people ask, 'will they hunt y'all downwardly? Aren't they dangerous?' People wonder if we're afraid of them."

"A lot of myths about them are way overblown," Aureate said. "People attribute magic powers to them, but they're just doing their thing, looking for food. They are curious, smart animals and they figure stuff out pretty quick. They are smart enough to run down a trap line, and that'll make trappers mad. Just information technology makes sense that they'd do that – in that location'south always nutrient on these trap lines. They're not extra aggressive, they avoid trouble."

Wolverines are weasels, Golden said, and have the weasel nature. "That whole family unit is pretty similar, just the size is unlike. Ermine can exist assuming; weasels are an intelligent family of animals and they know how to survive."

While wolverines are usually lonely, the "bad tempered loner" stereotype gives the impression they are downright antisocial. Golden visited a facility in Washington that'southward home to almost 40 wolverines. They shared a large common area and he said they were quite tolerant and social with each other.

"If resources are express that tin cause conflict, merely they can be social," Aureate said. "If nutrient is plentiful, they've got no reason to worry about each other. We've seen them in April from the air wrestling and playing with each other, they weren't fighting, they're socializing."

They are territorial, in the general sense of the word, simply Harrington and Golden apply the term "dwelling use area" to describe the surface area they favor. "They choice areas they maintain and go along to themselves, males will overlap with females, but males don't overlap much with males, or females with females," Harrington said. "They need resource, and they pick an area where they tin make a living and survive."

They have scent glands, a ventral gland near the omphalos, anal glands, and they also have little scent glands on the bottom of the pads of their feet, and when they walk they exit olfactory property. They also odor-marker through urination. "They basically maintain territory this way through active marking," Golden said. "We have found some that take been in fights and are scarred up, they do go into tussles. "

He said a wolverine tin can defend itself pretty well, just it's no match for larger predators. "Two wolves can impale one," he said. "You hear stories about them chasing bears off, I've never seen that happen, or known anyone who has."

Mike Harrington holds a young female wolverine. Wolverines are sexually dimorphic; males are well-nigh xxx percent larger than females - 30 to 40 pounds compared to females in the 20 to 25 pound range. This female, CWF006 has a blue ear tag and was meaning when she was defenseless on March vii, 2012. In this film she had just been recaptured to call up her neckband and is about to exist released.

Their eyesight and hearing are not especially good, but they have an outstanding sense of smell.

"They've got a pretty good gear up of tools on them; a really good nose, they tin can smell nutrient over long distances or buried well nether the snow," Gilded said. "They can climb copse. They have a really warm glaze. They've got potent claws for excavation and defense, and incredibly strong jaws for biting and crushing os and frozen meat - not the same burdensome power as a wolf, but they're non equally big, a large wolverine is xl pounds and small wolf is 60 pounds."

"You lot look at them, they're mostly built for scavenging," Golden said. "Merely they're very opportunistic and regularly impale modest game. They're not as fast every bit wolves, and they don't work in packs, but they can be more predator than scavenger if the situation allows for it."

Wolverines hunt snowshoe hares and voles, and in summertime ground squirrels and marmots are important prey items. "We've got documentation of them killing smaller Dall sheep. In Scandinavian countries they lose domestic sheep and reindeer to wolverines, and the government provides bounty to herders. The herders are required to hire rangers to document wolverine den sites and reproduction, and that'due south one reason they take great reproductive data."

It is true that wolverines are very strong for their size and take incredible stamina. Gilded said a wolverine can cover 30 miles in a night, working a circuit in search of food. They will den upwards and balance for cursory periods, and and then get back on the move. That ability to travel through incredibly rugged mountainous terrain is not exaggerated.

"That'due south the large thing to come out of the GPS work for Mike and I, and it's pretty amazing when you run into information technology," Golden said. "Nosotros get locations every 20 minutes, you tin can see how fast they movement around terrain, they go upwards and down really steep, icy, rocky slopes like they're not fifty-fifty there. Yous could never hike it – you'd need climbing gear. Information technology's similar they see the world every bit 2-dimensional, the way they move upwards and downwardly these snow-covered slopes."

Tracks in the snowfall

An innovative technique to assess population size has partly driven the inquiry. ADF&M biometrician Earl Becker developed a method to judge wolf populations based on aerial surveys of tracks in snow. Called SUPE, Sample Unit Probability Estimator, Becker worked out the technique for wolves and he worked with Gilt and Harrington to apply information technology to wolverines. Given some basic assumptions, it works like this: biologists survey an surface area after fresh snowfall and identify sets of tracks. The track lines can exist extrapolated to population numbers. Some bones assumptions must be met, for case, all animals of involvement movement during the written report, tracks are continuous, they're recognizable from the air, and pre and mail snowstorm tracks tin can be distinguished.

Wolverines bear differently from wolves, and they don't run in packs. An of import divergence is that a wolverine may sometimes sit down tight for two or three days, in a den site or on a impale, and that needs to be factored in.

Howard Gold fits a collar on a captured wolverine. Photo by Isabelle Thibault.

"For 2 or three days out of xx they might non exist moving, and if we did a SUPE at that time we might miss 10 or 15 percent that weren't moving after a fresh snowfall," Golden said. "That'southward a correction cistron we demand to use to the calculated estimate."

"The other thing almost SUPE, it only works in some areas," he added. "It wouldn't piece of work in Southeast; the canopy cover is too thick. You have to see that set of assumptions, and normally nosotros tin can verify them while we're flying."

Collaring and tracking wolverines allowed researchers to ground truth the technique – and learn a lot well-nigh wolverines in the process. Results from a cooperative study with Chugach National Forest indicated a wolverine density of 4.v to 5.0 wolverines per 1,000 square kilometers in Kenai Mountains and Turnagain Arm expanse, which is typical for other areas of South-primal where SUPES were conducted.

"Unlike techniques are suitable for certain areas," Gilt said. "In some areas yous're just looking for occupancy – do we even have wolverines?"

The researchers pointed out ii other methods used to written report wolverines. Hair snares subtly snag a tuft of fur from a passing animal, and the Dna in the follicles enables biologists to place individual animals, their gender and relatedness, and multiple samples over fourth dimension can provide a population approximate (mark-recapture). Photo identification uses remote, motility-triggered trail cameras to photograph animals in specific poses that reveal distinctive markings that can identify individuals – much as tail fluke marks are used to identify humpback whales.

Catching wolverines: traps and darts

The researchers captured xviii unlike wolverines between September 2007 and March 2014. Including recaptures, animals were live-trapped 14 times and helicopter-darted 10 times. Amongst the 18 wolverines captured, there were five juvenile (1–two years onetime) females, v adult females, four juvenile males and four adult males. Wolverines were captured in the Chugach Mountains east of Anchorage (in the land park), on the Elmendorf-Richardson joint base of operations (JBER) and s of Anchorage in the Kenai Mountains. The capture piece of work was washed in cooperation with Chugach Country Park, JBER Natural Resources Department, and Chugach National Wood.

Iii wolverines did not yield data – they slipped their collars right away, or for another reasons researchers were unable to discover signals. All the telemetry work was done in late wintertime and early on spring to ameliorate sympathise how wolverines movement during the period when SUPES are conducted.

Cameras proved to be a valuable tool for trapping and darting. Motion-triggered trail cameras were set near the live traps, and researchers wore helmet-mounted video cameras when helicopter darting to assistance them acquire from capture attempts. That helped them solve an equipment malfunction at 1 point in the project - they slowed the video down and watched it frame by frame, revealing a trouble with the dart design they were able to correct.

Darting can exist really efficient under ideal weather, and Gold said 1 twenty-four hour period they caught four wolverines. That was exceptional, some days they constitute wolverines they couldn't catch. Aircraft searched for roaming wolverines, and then chosen the capture team.

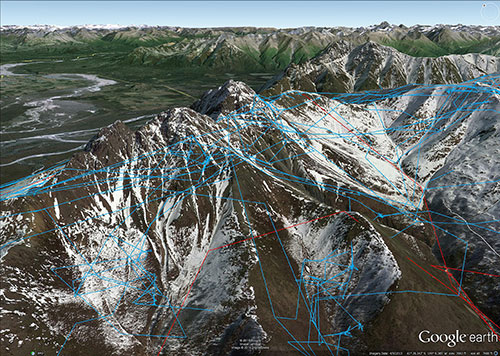

This Google World 3D map shows the movements of ii wolverines through the upper slopes and summits of the rugged Chugach Mountains. CWM006 is a male, and the carmine line shows his movements over about a month, betwixt his capture and collaring February. 21, 2013 and his last transmission March 26, 2013. The blue line shows the movements of CWF008, a female captured March 2, 2013 and her last transmission June 12, 2013, well-nigh a three-month period. "This is how they really piece of work in the three-dimensional world," Harrington said. "You really become a skillful appreciation when you see how steep it is and how they become up and down that rugged stuff."

"Wolverines are never very abundant, fifty-fifty when they're arable for the species," Aureate said. "Yous need good conditions to track them, we had two fixed-wing aircraft just looking for animals, sometimes for hours, and then we're sitting on a ridge with the helicopter, waiting. Then nosotros go the call and go after them."

Darting a moving creature from a moving helicopter is clearly a claiming. Harrington said the mountainous terrain and relatively minor size of the target added to the difficulty. One thing played to their advantage, he said when pursued, wolverines tended to run uphill. In deep snowfall that really hampered their speed.

"On difficult packed snow, we couldn't believe how fast they tin can run," he said.

Pursuit was express to 10 minutes. "Sometimes we had to say, 'we're not going to get this guy.'"

Once defenseless, wolverines were quickly processed. Throughout processing biologists monitored wolverines' temperature, heart charge per unit and respiration, and were prepared to provide supplemental oxygen if needed. They took samples of tissue (for Dna), pilus and blood, the animals were weighed and measured, age estimated, and they were marked with an ear tag and equipped with a GPS/VHF collar.

The collars were programmed to record GPS locations at xx-min intervals, and were capable of maintaining that rate of data drove for nigh 3 months and then to continue VHF beaconing for about 100 days longer before battery failure. Collars also stored altitude and air temperature. Two types of GPS collars were used; both stored thousands of location data points onboard and immune remote downloading of neckband information from the ground or from the air. One model could be released remotely to drop-off, the other could not and required recapture to retrieve collars.

Golden and Harrington were successful live-trapping on JBER during the offset 2 or three years while new animals were yet coming into the trapsites. The researchers took advantage of a winter moose hunting season on the joint base - wolverines were attracted to kill sites and worked the hunt areas into their foraging circuits. Nevertheless, information technology became very difficult to concenter wolverines into traps during winter of 2012–xiii, which they attributed generally to the lack of new wolverines visiting the area. From images gathered on the remote cameras, it seemed the animals were besides wary to be caught.

"They remember where they've found food, but they got wise to the traps really quick," Harrington said. "They're hard to live trap in the beginning place, and really difficult after that. Yous might fool them once, but how do you fool them once more after that? We got artistic with different kinds of bait - nosotros tried chickens wrapped in bacon, and large wads of beef suet."

Wide ranging

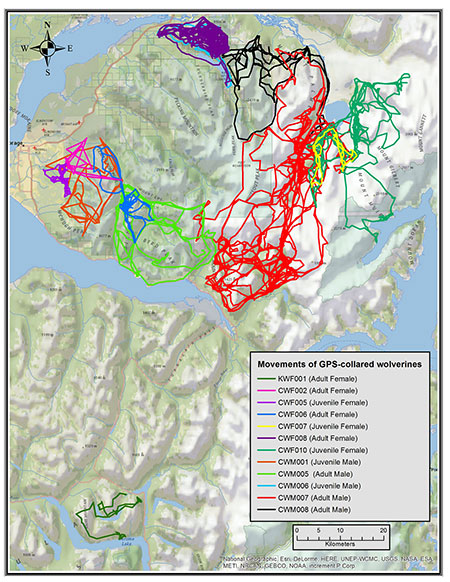

Dwelling house range estimates for wolverines in South-key Alaska show females employ almost 300 to 600 square kilometers (115-230 square miles) and males apply virtually 700 to 1,000 foursquare kilometers (270 to 380 square miles.

Movements of 11 wolverines in the Chugach Mountains east of Anchorage, and one wolverine on the Kenai Peninsula further s. Turnagain Arm is the water in the center left. Adult male person CWM007 is depicted in red and has a domicile apply expanse twice the size of other wolverines. Annotation the movements of the male person (CWM006) and female (CWF008) every bit shown on the other map of the mountain tops.

Males and females traveled extensively throughout their habitation use areas. Both sexes occasionally went on exploratory trips and so returned to their chief areas. A look at the movements of five wolverines over the course of a twelvemonth (two females and three males) showed smashing variation in distances traveled, some days they covered a lot of ground, others days not so much. The average distances traveled per day was about 12 kilometers for the females, and between 8 and 21 kilometers for the males.

"One male had twice equally big an surface area every bit other wolverines," Gilded said. "Information technology may exist that expanse had lost a male and this brute just took over the whole area, at least for the brusque fourth dimension the collar was agile."

Considering the focus of the report was movement in late winter and jump, the researchers did not track wolverines year-round. The far ranging male did provide some data in tardily bound – when he expanded his range even more.

"They do spend a lot of time in summertime during the convenance season testing boundaries and trying to encounter females," he said.

An important time in a wolverine'due south life, and a fourth dimension for significant movement, is when a young adult strikes out to establish its own home range. Wolverines are born in February or March, ii to four kits that usually dwindle from bloodshed to one or two by fall.

"Mortality is pretty loftier for kits," Golden said. "We're finding females generally don't have a litter earlier they're well-nigh three years former, and then typically have a litter most every other twelvemonth."

The kits are substantially full grown past October or November and begin moving out. It tin can be tough for a young wolverine to observe a territory that is unoccupied and suitable. "A girl might stay with mom a couple years and inherit her surface area," Golden said. "Young may try and stay relatively close to their natal area, and siblings may be more than tolerant of each other."

Just wolverines have been known to disperse as far as 235 miles. Dispersal is important, that's how wild areas that "produce" wolverines can supply them to potential dwelling house ranges elsewhere, good habitat where wolverines may take been harvested.

That residuum is a model for sustainable yield – enough refugia from human action, practiced habitat for wolverines that are producing immature that will emigrate out.

Hunters and trappers in Alaska harvest nearly 550 wolverines each year. Considering wolverine reproductive potential and survivorship is low it's important to sympathise where and when animals are harvested to be sure the population is not overharvested. Wolverines disperse depending on availability of food and habitat resources, and animals dispersing from areas where they are not trapped replenish the population in areas where they are hunted and trapped.

A gallery of trail camera photos of wolverines is available, as well every bit a short video of a wolverine raiding the nest of a ground-nesting shorebird and eating the eggs.

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News.

Receive a monthly observe most new issues and articles.

veitchcommoodle1982.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=692

0 Response to "The Wolverine Size of a Baby Wolverine Actually a Baby Wolverine Signs"

Post a Comment